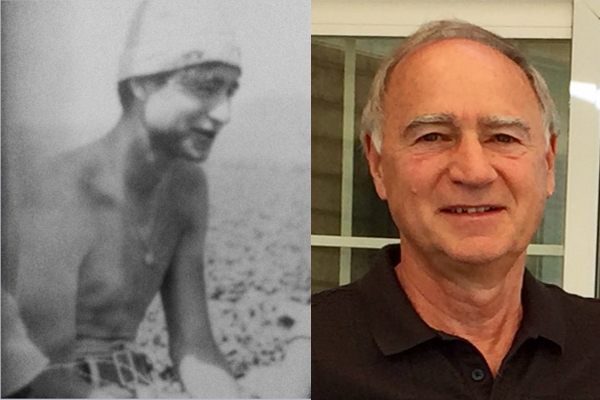

Photo from left: Manley after arriving at Kibbutz Dafna in June, 1967 and Manley today.

It was June 5, 1967. I awoke to an eerie, loud wail coming in through an open window. The room was bright, the sunshine pouring in through the window. Through sleepy, half-open eyes, I peered around the large room I was sharing with three other young men, all around my age, on the second floor of the nondescript hotel in Tel Aviv that we had been sent to the day before. The other beds were empty. The room was empty. No-one was to be seen or heard. I forced open my eyes, fully taking in my aloneness. What was going on? The shrill sound stopped abruptly but what was it?

I got up and almost immediately the sound started up again. I gradually realized it was a siren, or what I imagined was an air-raid siren, and walked over to the large open window to see what I could see. Our room was at the back of the hotel and the view, unfortunately, told me nothing. I saw no roads, no shops, no sidewalks. No one was walking around in the opening between my hotel and the other buildings in front of me, neither to the left nor the right. Nobody! Nothing!

What was going on and where were my roommates? It seemed such a long time since it had all started, roughly four weeks before…

It was mid-May, 1967, in an early morning mathematics class at the University of the Witwatersrand (WITS) in Johannesburg, South Africa. The lecture theater was a tiered, large, old-fashioned room, about 10 rows deep, each containing a long writing desk with the seats behind them, the rows gradually sloping upwards towards the back of the room. It was on the hour, and a half dozen students, myself included, sat huddled in the middle of the back row trying to listen to a small transistor radio one of us had brought to the class. We had to keep it low for fear the professor would hear the radio, but also loud enough for us to hear. We tried to listen to the whispers of the radio while pretending to listen to the lecture, simultaneously copying the copious notes written by the professor on the large, multi-sectioned blackboard in the front of the room.

In those days South Africa had no television. There were only two government-run radio stations, one in English, and one in Afrikaans, with a third, commercial station carrying mostly music. World news, roughly ten minutes long, was carried maybe four or five times a day. So, other than reading newspapers, getting up-to-date news required you to turn on a radio at exactly the right time. We, second-year Jewish, Zionist, mathematics students, had no other choice but to furtively listen in class to know what was happening.

Tensions had been rising in the Middle East, particularly between Israel and Syria. Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser was now demanding that U Thant, Secretary-General of the United Nations, remove the UN peacekeeping forces stationed in the Egyptian Sinai Desert, all the way up to Israel’s western Negev boundary. These UN troops had been there since the 1956 Suez War, forming an Egyptian-Israeli buffer zone in the Sinai. When U Thant complied, Nasser sent Egypt’s army across the Sinai Desert, and they were encamped along Israel’s border. And on another day in May we heard that, in violation of international law, Egypt had set up a blockade of the Straits of Tiran, thereby cutting off all shipping, especially vital oil shipments, destined for the southern port of Aqaba.

Things looked very ominous. War was on the horizon and seemed inevitable. Israel was calling up reservists to supplement its standing military and its soldiers in training. At the age of 18, following high school, every Israeli was required to enter military service – 30 months for men, 18 months for women. After fulfilling their duty, Israelis were considered reservists until their 50s and could be called up at any time.

As young Zionists in South Africa, we were in a state of unrest. What was going to happen? What could we do to help? Most of us belonged to one or other of the Zionist Youth movements active at that time. The movements were co-ed and similar to scouting groups (for Jewish youth). The largest were Habonim, affiliated with the Socialist party governing Israel, and Betar, associated with the Revisionist party, the main opposition in Israel, but there were a few others as well, (for example Bnei Akivah and Hashomer Ha-Tzair). Each had an ideological basis but I, and most of the youth I knew, were part of one or other movement for social reasons; for example, one’s friends belonged, or meetings were close to home, or one’s parents had belonged in their youth, and so on.

The older teens met weekly on Sunday nights to partake in various activities and to socialize. During this crisis many knowledgeable, Jewish community leaders who had connections in Israel came and spoke to us, updating us on the situation in Israel. In addition to the serious security situation, by far the biggest crisis was to Israel’s economy. With all the reservists being called up, Israel’s all-important agricultural industry was in dire straits. The business sector, of course, was also in trouble. But what could we do? Appeals for financial donations for Israel poured into the Jewish community, and many people contributed.

Egypt’s Nasser was very busy with the Pan-Arab alliance, meeting with the Jordanians, the Syrians, and other Arab countries to plan a campaign for the annihilation of Israel. Of these, the most dangerous to Israel were the Jordanians (reinforced by the arrival of Iraqi troops) and the Syrians. After 1948, the Jordanians had annexed the West Bank between Israel’s eastern border and the Jordan River, and so their troops threatened Israel’s heartland and population centers, its industrial centers, and Israel’s modern and largest city, Tel Aviv. The Syrians were massed on the Golan Heights, the northeast border with Israel.

These heights overlooked and threatened the agricultural settlements hundreds of feet below, in the Galilee plain – very vulnerable to attack and to being overrun. To the north, Lebanon was slightly more westernized, had its own social and political problems and did not have a very large army. So it could be contained but, nonetheless, was still a serious threat. If the Saudis got involved, they could join up with the Egyptian army at the narrow southern tip of Israel, at the port city of Aqaba, and take over the southern Negev Desert.

At its narrowest point, Israel is less than 10 miles wide, and the Arab goal of pushing the Jews into the sea seemed attainable at last. The situation was dire, and things did not look good.

Towards the end of May, we began to hear rumors of “volunteers” going to Israel but for what purpose, whether to fight in the army or some other capacity, was not at all clear and the subject of much speculation. Word quickly spread that the South African Jewish Board of Deputies, the umbrella organization of the South African Jewish community, was to hold a meeting on the evening of Saturday, May 27, at the Zionist Federation Center in Johannesburg, where we would find out more.

I remember that, on Friday night, May 26, after a family Shabbat dinner, my father and I went for a walk around our neighborhood. It was a warm evening, the sky was clear, and we could see the multitudes of stars visible in the Southern Hemisphere, the Southern Cross and other constellations. I had previous expressed my desire that, should Israel need volunteers, I would like to go. Being 18, I would require the permission of my parents (in South Africa the age of majority was 21). Even though I sensed my father was sympathetic to my wishes, I was certain my parents would not give permission, should I have to join Israel’s army or engage in any sort of fighting.

However, I also understood my parents’ conflict. I was born in 1948, two months after the declaration of the modern state of Israel. Israel, Zionism, and the birth, growth, maturity and, in particular, the destiny and survival of Israel was the mother’s milk of my world-view. When I was born my uncle, Dave Magid, (then 25 and engaged to my mother’s sister Frouma), arrived at the hospital to say goodbye to my mother. He and his brother, Eddie, were leaving for Israel to join its newly- formed army in Israel’s fight for survival in what came to be called Israel’s War of Independence. The story of how Dave came to visit my mother in hospital to say goodbye was a legend in our family and household. Both he and Eddie survived the fighting and, I think, my mother, in particular, recognized that my desire to take part in ensuring Israel’s survival was partially a fulfillment of my destiny and something I would have to do. But she wasn’t happy about it!

While walking and discussing the recent events, my father suddenly asked me what I thought would happen if all of Israel’s enemies attacked at once. I had to think about that – in my youthful zeal I had not given it much thought before. After walking a little while longer, I answered that I thought that, if a few of the countries attacked, Israel’s army was strong enough to repel them but I supposed that if all the Arab countries attacked at once, it was possible that Israel would be overcome and annihilated. As I said this, I was awash with emotions and silent thoughts. Here I was saying that, if my father gave me permission to go, and if all Israel’s enemies attacked at once, Israel would be destroyed and I could be killed. He would never see his only son again. I could not imagine what was going on in his mind as I answered him.

On Saturday night, May 27, the meeting was packed with parents, young adults, and children. South Africa’s Jewish community at the time was estimated to be roughly 125,000, nearly half of which lived in and around Johannesburg. It seemed like almost the entire community was there. After various updates of the situation in Israel, the announcement came that Israel’s Jewish Agency had issued a call for volunteers to come to Israel in its moment of need. It was emphasized that this was not a call for military volunteers but rather for young people to come and engage in agricultural work in the fields, the labor that had had to be abandoned by the call-up of the Israeli army reservists. We would be sent to kibbutzim, moshavim, or other agricultural settlements to engage in agricultural labor. We were asked to meet with our youth movements the following Sunday night, when representatives from the Zionist organizations would attend to answer questions and to get a sense of the members’ desire to volunteer.

During the next day, Sunday, I had serious discussions with my parents. They asked me not to rush anything but, now that volunteers were not going to have to engage in military actions, they were more willing to give me permission to go. Of course, we all recognized, without stating it out loud, that should war break out and Israel start to lose, volunteers would no doubt get caught up in fighting, and some would never return.

Then my mother raised another obstacle. We were approaching the middle of the academic year and I was a second-year student at WITS. If I went to Israel, I would have to abandon my studies. What then? The university system in South Africa was similar to the British university system. Academic courses were not divided into quarter or semester units but ran for the entire academic year with a massive final exam on the entire year’s work at the end of the year. In addition, getting into a university was competitive. Not every high school graduate was admitted to a university, let alone one of the country’s top universities. If I abandoned my studies not only would I have to repeat the entire year when readmitted, but there was a more-than-likely possibility I would not even be readmitted at all.

At the Sunday night meeting on May 28, after answering our questions, the Israeli representatives told that there was a possibility the first planeload of volunteers would be leaving on Saturday, June 3, in just six days time. I expressed my interest in volunteering but needed to check on my academic situation first. I was told to let them know as soon as I could the next day, or else I could not be on the Saturday flight.

The rest of that week was a blur of activity. The first thing I did on Monday morning was go to the university to speak with the Dean of the Faculty of Science (as the college of my studies was called). He wasn’t in and I was told to make an appointment for the next day. When I cried out my urgency, the dean’s secretary relented, and I was directed to a hothouse on campus. The dean was a biologist, actively engaged in research, and busy with his projects that day.

I entered the hothouse, and can still remember being surrounded by tables of plants and greenery. At one end stood the dean, a kind-looking man, with a sprayer in his hand. He was surprised to see anyone entering the greenhouse, but I introduced myself and explained that I needed assurance that, if I left the university immediately, around the middle of the year, before mid-year exams, I would be readmitted into the second-year program when I returned. To my great relief, he was entirely supportive of what I was trying to do and gave me assurances that I would indeed be readmitted into WITS. He told me to go back to his college office and tell the secretary what he had told me, that she was to write in my file that I was leaving WITS and should be readmitted. That was that! As far as I can recall I was not given a written assurance but it was understood that, since he had given his word, so it would be!

I immediately left, went to the Zionist Federation office, and put my name on the list of volunteers from my youth movement. Now another big obstacle emerged. I needed a passport. In the South Africa of those days getting a passport was a bureaucratic nightmare that could take many, many months. Multiple forms, photos, tickets to prove travel plans and reasons for travel, a source of financial support while away (since currency restrictions in South Africa only allowed a limited amount to be taken from the country) were needed. Also, Wednesday was May 31, Republic Day, a national holiday when no government offices would be open or working. How would it be possible to get a passport within three days, before Saturday?

To South Africa’s credit, the government expedited the entire process. Monday afternoon I went to get my passport photos, and the photo company agreed to rush it so I would have them on Tuesday. Tuesday I took my photos and went to apply for a passport. I filled out the forms. No other supporting documentation was needed. I was told the passport would be ready Friday morning – amazing! The rest of the week was spent running around doing various last-minute shopping chores, meeting friends and family to say goodbye, meetings at the youth movement house, at the Zionist Federation office, meetings with various officials.

Finally, Saturday night came and I was ready. The departure lounge at Jan Smuts Airport in Johannesburg was a mob scene. More than 50 volunteers were leaving on that first flight, and families, extended families, and friends, plus other well-wishers from the youth movements, were there to see the volunteers off. Finally came the hour to board. We passed through the gate and walked in the semi-darkness across the tarmac to the stairway of the plane ahead. As we walked, we looked backward and waved at who-knows-who standing at the large window of the departure lounge, overlooking the runway, where we saw a mob of people waving frantically at us. Suddenly, before we reached the plane, a police escort that I hadn’t noticed called us to attention. We stopped in our tracks, turned around and heard the officer in charge call his men on the tarmac to attention. With our backs to the plane we followed along, singing aloud the (then) South African national anthem, “Die Stem.” After that, without police prompting, we continued standing at attention and broke out into a spontaneous, emotion-filled rendition of “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem. Then we boarded and left. It was the first time that I, and most of the others, had flown on an airplane.

On Sunday, June 4, we arrived mid-morning at what was then called Lod Airport, near Tel Aviv. I was lucky that my older sister, Ruth, was living in Israel, and she and her husband and in-laws met me in the arrival lounge with hugs, gifts of clothing and well-wishes. We were also met by representatives of the Jewish Agency and given a card hand-printed with the name of our destination. Members of the various youth organizations were naturally kept together. Some were to go by bus immediately to Kibbutz Me’en Baruch in the Upper Galilee, some to other destinations. They all boarded their buses and left immediately, without any fanfare. The roughly 12 members of the group I was with were to go to Moshav Amatzia near Jerusalem, located adjacent to the (West Bank) border with Jordan. To our surprise, we were told we would not be going right away but would leave the next day. We were told we would be put up for the night in a small hotel in Tel Aviv, the hotel from whose window I now peered, on Monday morning, June 5, wondering what was going on and where my roommates were…

Had I overslept? Had they all left for Amatzia without me, not realizing that I was not on the bus? I immediately dressed and went downstairs. To my relief, on entering the small dining room, I saw my comrades sitting around, talking in excitement about what was happening.

The war had started! My roommates had been woken earlier by the sound of a single siren. They were told it was an air raid siren, and they had to go to the basement bomb shelter. I was still asleep, and no one had thought to wake me! And so I blissfully remained sleeping through the beginning of the war. What apparently had woken me was the first wail of the all-clear siren, some thirty minutes later. No bombs had been dropped – indeed planes had barely been heard. It turns out the air raid siren was a cautionary warning to the Tel Aviv residents to get into their bomb shelters as the war began. There was much nervous speculation, as none of us knew what was going on or what was going to happen to us.

After a short breakfast, the Agency’s representatives came in to let us know that we would not, after all, be going to Moshav Amatzia. War had started that morning and Amatzia was too close to Jordan and the fighting. We would instead be going to Moshav Misgav Dov, south of Tel Aviv. We correctly concluded that we had not been permitted to go to Amatzia the day before because the Israeli military had known an attack by Israel was planned for Monday morning, June 5, and had prohibited any travel to the border areas. That was why we had been sent to Tel Aviv, and why other arrangements had had to be made for us.

So off we went. I lived in Misgav Dov with a poor family whose oldest son had been called up for the war. They desperately needed someone to help with maintaining their agricultural fields and with feeding their cows. They spoke not a word of English so I made do with my erratic Hebrew. We only saw some military activity in two days, once on Monday after we arrived, and on Tuesday, when, from far away, we saw Israeli Air Force planes flying over the Mediterranean towards the Egypt-occupied Gaza Strip and the Sinai.

I worked fairly hard in the fields but enjoyed the evenings, walking around and talking with my fellow volunteers. We met some younger Israelis still in high school. One, in particular, engaged me in Hebrew conversation, and I still remember talking with him one evening, when suddenly all the Hebrew grammar and vocabulary I had learned in high school in South Africa kicked into gear and came together. Suddenly I was conversing quite smoothly in Hebrew without thinking about it. It was one of those aha! moments one reads about.

The war ended after six days, on June 10. The following Wednesday, June 14, the Jewish Agency took us on a tour of the newly united Jerusalem, the Western Wall and through the West Bank. It was still a militarized zone, so we were forbidden from bringing our cameras. Afterward, we were told to pack our bags, and the next day we were taken by bus to work in Kibbutz Dafna in the Upper Galilee, not far from Me’en Baruch and the Golan Heights. While there we were also taken on a tour of the Golan Heights and the much-damaged Syrian town of Kunetra, where we saw much military destruction and abandoned military hardware in the fields.

There were many jobs to do on the kibbutz. The one I enjoyed the most was also the hardest: we called it “kash” (Hebrew for “straw” and rhymes with “rush”), involving working in the wheat fields. Since others shied away from it, four other like-minded friends and I were always able to get assigned to this job, especially when, after a few weeks, I was asked to take over the nightly scheduling of the volunteers’ labor assignments for the following day. I enjoyed “kash” because it was very physical and active, unlike, say, cotton-field work or picking fruit.

Because of the intense summer heat in the afternoon, we had to get up extremely early, before anyone else. We climbed into the back of a truck, and the kibbutz member assigned to oversee us drove us to the fields to load very heavy bales of straw onto the truck, then drove us back to the kibbutz where we unloaded the bales into a pyramid structure, and then drove us back for another load to do it over again. The loads were so huge, the truck so top-heavy with bales of straw, that with the truck swaying from side to side, we drove back to the kibbutz very slowly.

After the second load had been deposited, it was lunchtime. We were hot, sweaty and exhausted, and had already worked for eight hours, so we were done for the day. We had the whole afternoon to ourselves to swim in the kibbutz pool, or to relax, sleep, or whatever.

After two months at Kibbutz Dafna, our group was again moved, this time to Jerusalem. There we lived in Har Tzion, Mount Zion, in a two-story, rectangular, brick house with a flat roof. Before the war, Israeli soldiers had occupied this house, as it was right at the former border with Jordan. On two sides its walls were pock-marked with deep bullet holes. From its flat roof one could see, no more than 50 yards away, a former Jordanian military encampment. When we went down to visit it, we discovered its paths had been paved with tombstones taken from the ancient Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives, which had been desecrated while under Jordanian occupation.

The house was located close to David’s tomb, and one day after work, while visiting this structure, I discovered a short-cut through the tomb buildings, along a narrow path, past the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, whose cone-shaped roof had a hole from a shell right through it. I was then in the Old City of Jerusalem and found the road to take me to the Jaffa Gate, and from there on to the new city from where I could take a bus to visit relatives who lived in Jerusalem. I did this so often that eventually, when I returned home late at night, I could find my way through the unlit, dark streets of the Old City, feel my way through David’s tomb in pitch darkness, and finally get back to the house. Quite an adventure really!

Our work on Mount Zion and the Old City consisted mainly of a variety of odd jobs. We spent many days cleaning up the main square on Mt. Zion that was covered with the refuse of war. One day a busload of American tourists stopped near us and we pretended to be Israeli laborers who could not speak English. They poured out of their bus with their still and 8mm movie cameras, excited to film Israelis doing an honest day’s labor in the service of their country! Eventually, someone caved in and told them who we were, and we had a wonderful conversation with them.

On another occasion, an amazing coincidence occurred. It was around the Jewish Festival of Succot or Tabernacles. We were asked to assist a religious Jewish charity group based on Mt. Zion with their international solicitations of money for charity. Our job was to take a flyer, fold it with small paper items from Israel, and insert and seal the result into a pre-addressed envelope. We were seated at a table with hundreds of pre-addressed envelopes in the middle and dozens of flyers in front of us. The addresses on the envelopes were mostly in England and the USA, obtained no doubt when people had previously contributed to the charity.

Out of curiosity, we would look at the addresses as we sealed the envelopes – our geographical knowledge of the United States and England was rather sketchy, and very few of the cities and states had any meaning for us. Occasionally an address in another country or part of the world would appear, even some from South Africa. Suddenly I let out a screech! There, right in front of my nose, was an envelope with my mother’s name and our address in South Africa! I could barely believe it and showed it around to my co-workers. Of all the hundreds of envelopes there, what were the odds? I quickly got a pen and wrote her a brief message and sealed the result in her envelope.

Finally, after roughly two months in Jerusalem, we were told to get ready for our return to South Africa in a few weeks. With about 10 days to go, five of my friends and I were given permission to go on a six-day trip to Turkey, via Cyprus, by ship. After a few more days with family, I flew back to South Africa, arriving early in November. This was an experience never to be forgotten!

Postscript

- The South African Jewish community, at that time totaling roughly 125,000, was very pro-Zionist. The number of volunteers South Africa sent to Israel during and after the Six-Day War, while not the most numerous of all countries, was the largest, relative to the size of its Jewish population.

- In February 1968, I returned to restart my second year at WITS. To my surprise, one of my classmates in a statistics class, a young student whom I had admired from afar the year before, was also in the class. What had happened? Had she failed the class the year before and was now repeating it? Eventually, I got up the courage to ask her. Turns out she, too, had been a volunteer in Israel the year before. She’d not been on my flight but had arrived right after the war, stationed at Kibbutz Me’en Baruch. I’d had no idea. Eventually, we started to date and, to cut a long story short, we married in South Africa on July 4, 1971, moved to the U.S.A. and have lived here ever since. A reward for my volunteer service!!