On Feb. 21 the Holocaust History Center re-opens with a new exhibition titled “Intimate Histories” on the campus of the Jewish History Museum in downtown Tucson.

This re-opening follows the 18-month run of the inaugural exhibition of the Holocaust History Center in a 407-square-foot space adjacent to the Jewish History Museum. The inaugural exhibit, which featured the stories of more than 200 Holocaust survivors who live or had lived in Southern Arizona, attracted some 2,000 students and more than 5,000 visitors during its run.

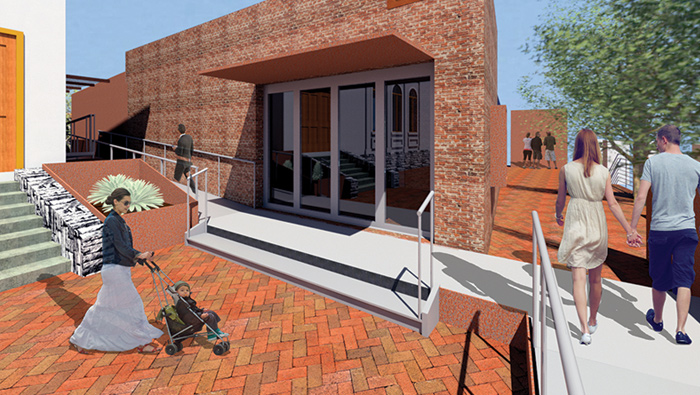

The overwhelming reception of the inaugural exhibition, titled “Those Who Were There,” led to a lead gift that ignited a capital project in 2015. The project’s goal is to increase the size of the Holocaust History Center five-fold and renovate the entire Jewish History Museum campus into a contiguous and fluid space where Jewish culture would live and memory would be preserved. The renovated campus will feature sculpture and memorial gardens and numerous architectural features that maximize potential for learning, reflection and inspiration.

The design process has evolved from early grandiose concepts that relied heavily on technology, to a more intimate approach. The carefully curated spaces will gradually illuminate how forces such as totalitarianism and anti-Semitism impact individuals, families and societies while reminding visitors that these forces continue to influence the world today.

That shift toward intimacy as a guiding design principle arose during the summer of 2015 when members of our design team read Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space (1958). In the book, Bachelard asks, “How do we unite exterior realities with intimate realities?” The design team understood this question as similar to asking, “How do you represent the effect of the overwhelming magnitude of history and power on the individual who history and power so often render mute, anonymous and invisible?”

The most precious and tangible materials we have to respond to this challenge are the testimonials from local survivors. The core exhibit at the center will feature local survivor video testimonials; it includes interviews conducted by the Jewish Federation of Southern Arizona over the course of several decades and the 54 interviews of local Holocaust survivors conducted and archived by the USC Shoah Foundation in the mid-1990s.

Initial designs for this core exhibit featured a wall full of video monitors that abutted one another, and that would act independently, each displaying one testimonial video, or in concert to create a larger contiguous image. The exhibit would have been highly technologically interactive with individual audio controls and headsets for each visitor. While this approach was visually and technologically mesmerizing, it would not achieve our primary aim of allowing visitors to immerse themselves in these micro-histories.

Another reading factored into the redesign of this core exhibit. In his book Dossier K., Imre Kertesz, a Nobel Prize-winning author and survivor of Auschwitz and Buchenwald writes, “It is painful to carry the brand of surviving for some unaccountable reason. You are invited to attend anniversaries; your irresolute face is video recorded, your faltering voice, you hardly notice that you’ve become a kitsch supporting character in a fraudulent narrative.”

This sentiment articulated by Kertesz haunted our design process. In response, we created the survivor memorial exhibit being sensitive to the dangers of smothering truth with sentimentality. Our intent was to remain faithful to the testimonial truths spoken by those featured in the exhibit.

The design of the exhibit evolved in a way that aligns with our guiding principle of intimacy. Rather than the visual distraction of gazing at dozens of faces while standing in an open exhibition hall, we settled on a theater-like space where one testimonial video at a time will be presented on a large projection screen. Visitors will be able to sit in an individual section of the center and receive the testimonials privately. This design also adheres to the pedagogical charge to work against anonymity and to translate staggering statistics into one human life at a time.

Another exhibit in the center will walk visitors through the eight stages of genocide in eight consecutive exhibit spaces. Each section will use a variety of media and artifacts to demonstrate how qualities such as hate speech, propaganda and the promotion of us-versus-them dichotomies can lead a society toward catastrophic consequences. The intimate experience of this exhibit reveals how the early stages of genocide are in some instances strikingly close to today’s realities. In other words, the exhibit guides us to look at ourselves in the present rather than look over our shoulders at the past.

In the center of the campus, in an enclosed outdoor space, a private remembrance room will provide visitors a place to reflect on all they have encountered across the campus and to enact Jewish memorial traditions. Yahrzeit candles will burn in the remembrance room, and containers of crushed stone will allow visitors to carry out the tradition of marking their remembrance by placing stones onto a ledge as part of an ongoing vigil.

Materials were carefully chosen to complement the exhibit’s design. The dominating presence of raw steel throughout the center reflects the industrial characteristic of the Nazi’s genocidal process. Repurposed materials, including 120-year-old wood reclaimed from the building’s interior and basalt stone salvaged from the building’s original foundation, provide authenticity and historic qualities.

The spatial design of the new campus will take visitors through a sequence of tension and release thresholds. This sequence of movements is intended as a physical metaphor of the dramatic back-and-forth shifts from hope to despair, freedom to imprisonment that victims of Nazism experienced. Visitors will simultaneously experience a movement from darkness to light with the end of the exhibit leading them out to the memorial garden where views of the mountains to the west and the Sonoran sky above will provide a private place for quiet reflection.

Bryan Davis is interim director of the Jewish History Museum, as well as the director of the Jewish Community Relations Council of the Jewish Federation of Southern Arizona.