“Mommy has a disease,” I hear my husband explaining to my 12-year-old son. I can’t quite make out the rest of the conversation through my quiet sobbing upstairs in the bedroom. But I catch some of it. “Will she be OK?” Eli asks. “Will I have the disease too? Will I have to take medicine for it?”

I am ashamed and heartbroken that my son needs to learn about the bipolar disorder I’ve battled my whole life. As an advocate for those who suffer from mental illness and a staunch supporter of removing the stigma attached to brain disorders, I am surprisingly filled with the same mortification and sorrow I often rail against as I hear my husband explaining this illness to my youngest child. But the reality seems clear. I am struggling mightily and it is painfully obvious to my son that something is wrong.

Since our recent move from Phoenix to Seattle, life has been challenging for all of us. The anxiety of moving, coupled with the lack of friends, family and support system has sent me into a phase of my illness more severe than ever before. It started with an inability to sleep. After several weeks of insomnia, my emotions became overwhelming. For years, the right medication, exercise and counseling have allowed me to live virtually symptom free. There was really no need to inform my kids about the condition. But the incessant crying and unrelenting wakefulness have made secrecy no longer viable. I shared the truth with my 16-year-old son several years ago when we noticed his severe anxiety and recognized the need to address it. But somehow I never thought I’d need to tell Eli, like I’d been cured and no longer needed to be branded with the mental illness label.

It troubles me that I felt the need to hide this reality from my son. I would openly tell anyone suffering from any type of mood disorder that it is nothing to be ashamed of, that having a brain disorder is like any other organ problem, that no one would think twice about taking medication for seizures or diabetes. But when it came right down to it, I was embarrassed and felt like a personal failure for having succumbed to a disease that I had convinced myself I had fully overcome.

I remember clearly the day I learned about bipolar disorder. It was after a painful period in my 20s that nearly ended my life. I miraculously discovered a book entitled You Mean I Don’t Have to Feel This Way? by Colette Dowling. Reading it gave me hope and allowed me to forgive myself and recognize that this malady had nothing to do with personal weakness or a lack of trying to “get better” on my own.

Back when I was first diagnosed, my father, a pharmacist and owner of a small retail drugstore chain, was horrified. He had built his entire life on the belief in the power of medicine and its ability to heal people. But the idea that his own daughter suffered from something “mental” or “emotional” was too challenging for him to face. My first medication was a SSRI (serotonin specific reuptake inhibitor) known as fluoxetine (aka Prozac). It was relatively new and exceedingly expensive. My dad could have easily reached out to one of his distributors for a wholesale price on the drug. But his shame overtook his practicality and he preferred to pay full price rather than reveal anything so personal and embarrassing to one of his colleagues.

I wasn’t sure how to take my father’s shame. It made me feel defeated, like I was an embarrassment to my family. It was obvious that I had let my parents down. Over the years, I learned more about my illness and personal brain chemistry, which helped me understand the critical role of psychopharmaceuticals in combating the pain and hopelessness of mental illness. On many occasions I’ve tried desperately to counsel, encourage and support people facing the same guilt and indignity that confronted me as a young woman.

But it is astonishing how quickly the past can resurface, even decades later. I wonder if Eli now thinks differently of his mother. I wonder if he is somehow disappointed in me. I wonder how he will cope with the possibility that his magical creative spirit and volatile temperament may hold some link to my genetic code.

Questions race through my mind at lightning speed. I am suddenly uncertain about my ability to function as a parent and professional. The only thing that seems clear to me is that while times have changed, the issue of mental illness is still a tricky topic to address. The fear of judgment and criticism, along with the negative self-talk that accompanies mental illness is still palpable. My only hope is that as those of us who fight these battles continue to be open and honest with the people around us, we will further sway the societal consciousness and help build a stigma-free world where brain disorders and their management are no longer something to hide, but instead treated like any other biological infirmity.

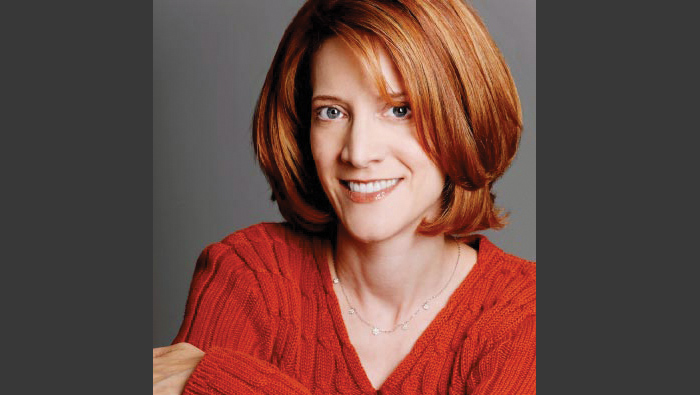

Debra Rich Gettleman is a mother, blogger, actor and playwright. For more of her work, visit unmotherlyinsights.com