It’s a parent’s worst nightmare. Your 17-year-old son comes home from high school not able to distinguish reality from fantasy. You panic. Alcohol? Drugs? How did you miss the signs?

You immediately kick into action and take him to the doctor, the psychologist, the psychiatrist. He ends up with a series of diagnoses over the next month: bipolar disorder, substance abuse, mood disorder, attention deficit disorder – or all of the above with hyperactivity.

He seems to erupt into psychotic episodes monthly. What is happening? Then one day at a routine psychiatric visit he becomes exhausted and simply has to lie down and sleep. The doctor is concerned about him driving in this condition and calls you to tell you what’s going on. She mentions “hypersomnolence” and you shift into research mode.

This is the story of Randi Jablin and her son Mathew Sherman. After hours of research back in 2013, Randi discovered that hypersomnolence is a symptom of a rare neurological sleep disorder known as Kleine-Levin Syndrome. “As I read the symptoms,” Randi tells me, “I kept seeing the same symptoms that Mathew was exhibiting: periodic episodes of hypersomnia, compulsive eating, cognitive impairment. I said to myself, ‘This has to be it!’ ”

The more Randi learned about Kleine-Levin Syndrome, the more convinced she was that her son was afflicted with KLS. Then she discovered that there is an Ashkenazi Jewish genetic link to the disorder. There is no treatment. There is no cure. The disease seems to show up mysteriously in the late teens and disappear just as mysteriously, usually when the patient is in his 20s.

Mathew went through a myriad of tests: EEG, MRI, sleep studies. Everything indicated normal brain activity. But Randi was convinced it was KLS, which can only be diagnosed by excluding all other possible illnesses. She printed off articles and presented them to Mathew’s team of doctors. While not a single doctor had ever heard of KLS, they all concurred that Mathew’s symptoms indicated that he did have the disorder.

“How many people out there may be walking around with this disease and be misdiagnosed because no one has heard of this?” Randi asks. She then goes on to explain her determination “to educate as many people about it as possible.”

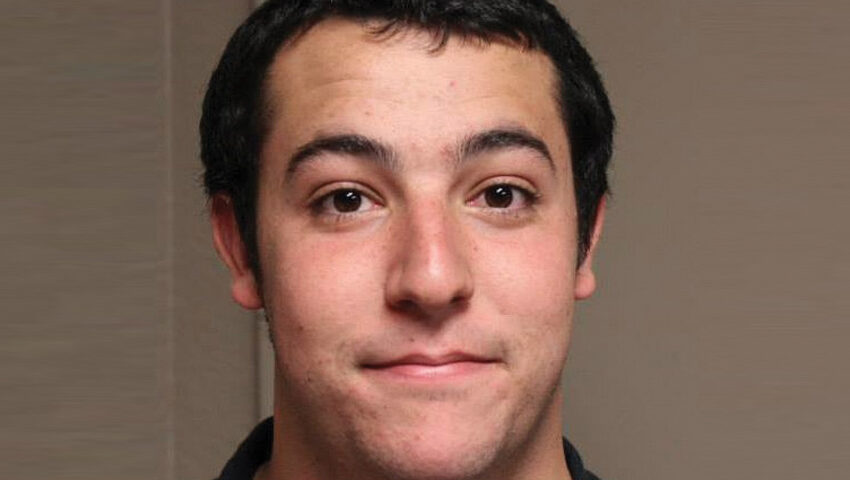

Today Mathew is 21 and coping well with his disorder. He recently came out about it on Facebook, which has helped both him and his mother in alleviating the stress, shame and secrecy surrounding Mathew’s illness. There’s even a Facebook support group for KLS sufferers. Finding others who share the symptoms of this rare disorder has given Mathew some piece of mind.

“He feels a sense of relief when he can talk to others who are experiencing the same things that he is during episodes,” says Randi. The Internet has provided Mathew with the knowledge that he is not alone and that there is a community of people who understand and support him on his path to wellness.

Mathew had planned to attend an out-of-state university before being stricken with KLS. He chose instead to stay in Arizona for college to keep his family and support network close by. As a junior at Arizona State University, he has been living successfully on campus and attending classes with minimal interruption. “During his first several episodes,” Randi candidly offers, “Mathew needed to be monitored 24/7. But now, he and I have this down to a science.” Randi makes sure to have a key to Mathew’s apartment and cell phone numbers for roommates and close friends in case of emergency. “He has accommodations through the ASU Disability Resource Center so that his teachers are aware of his situation.” Randi is proud of her son’s ability to manage his disease and maintain an impressive 3.5 GPA. Mathew does miss out on certain college experiences like drinking and all-nighters, as both alcohol and lack of sleep can trigger KLS episodes. He also decided to skip his planned Birthright trip because of the sleep-deprivation likelihood. These are tough decisions for a young man to make. But Mathew is committed to his wellness routine and continues to do well because of it.

He’s been taking lithium for about a year and has gone the longest ever between episodes. Randi isn’t sure if it’s the drug or his aging out of the disease. “Perhaps it is because I was in Israel during his last episode, and I started saying a Mishebeirach and have said one ever since when I’m praying in a synagogue,” she says.

As of today, there is no cure for KLS. But Stanford University has been studying the disorder for several years. Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa has also been involved in several sleep studies related to KLS. China, too, has become a partner in KLS research.

When I ask Randi what she wants people to know about KLS, she says, “I’d like them to be aware of the main symptoms so that if they hear of anyone who may be exhibiting these symptoms, they might be able to direct those people to KLS to see if that could be what the person has. Also, I want people to know that there could be a Jewish genetic link to KLS.” Randi mentions a study that found 17% of KLS sufferers living in Israel.

For more information or to make a donation to KLS, visit the website at klsfoundation.org. You can also see a video Mathew made about coping with KLS on the website.