In the late 1980s, under the leadership of Rabbi Bill Berk, Temple Chai set out to redesign the synagogue experience and create a more compassionate and compelling institution. At the forefront of this experiment was the notion that synagogue life should integrate healing and wholeness into the core of Jewish religious experience.

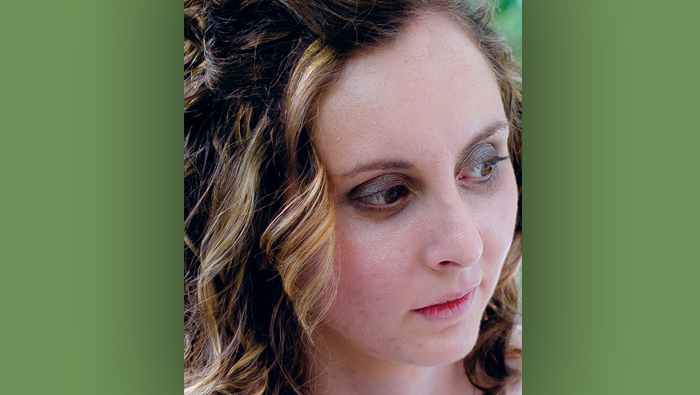

The experiment was successful, and in 1996 the Temple Chai Shalom Center was established with Sharona Silverman serving as its director. Today it is known as the Deutsch Family Shalom Center and is a dedicated resource center for the Phoenix Jewish community, providing healing, learning and community support through workshops, educational programs, support groups and a variety of communal spiritual development opportunities.

Sharona explains her impetus for starting the healing center. “It comes from my strong belief that no one can heal alone. My own experience of losing a father as a young adult, raising a child with a disability and having major spinal fusion surgery for scoliosis at the age of 40 prompted me to gain knowledge and comfort in the healing tools within Judaism that can transform these challenges and give them more meaning for growth and change.”

As a health care professional and educator, Sharona was faced with her own spiritual challenges in 1985 when her youngest daughter, Arielle, was born with a genetic disorder known as Leber’s congenital amaurosis, a retinal disease that causes blindness. Arielle, now an accomplished 30-year-old Ph.D. and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Washington, was born sightless. Together, she and her family have grown to view disabilities with a unique perspective that not only empowers their family, but also works to change the overall view of those with disabilities and to create a more inclusive and harmonious culture that better integrates them into every aspect of society.

When asked about raising a child with a disability, Sharona says, “I believe that every human being has their abilities and disabilities, and it is all a matter of perspective and attitude. Every life has its challenges, and we have the opportunity to use these experiences for growth. I have always felt this way, but raising a child with a disability brings it upfront and close.”

Arielle shares her mother’s philosophy. “A disability arises when a person who deviates from the norm in some way enters an unsupportive environment,” she says. “In other words, ability or disability is an interaction between a person and an environment.”

For example, Arielle explains that most people become disabled in environments lacking food and water, and racial minorities become disabled in racist environments. The idea here is that people with bodily features that deviate from the norm are only disabled to the extent that their environments lack the support they need to adequately function. “I use the words ‘disabled’ and ‘disability’ to refer to the environmentally imposed limitations, not to the physical differences,” she says.

Arielle is a rising star in academia, and her CV lists an impressive array of peer-reviewed publications, book chapters, speeches, journals, grants, and teaching and consulting experience. In her current position, she analyzes survey data that track the psychological experience of people aging with long-term disabilities. “I am interested in generating knowledge about what helps people remain happy, productive members of their communities as they experience disability,” she says. “I believe that all people have the capacity and drive to live full lives. Unfortunately, many of us with disabilities get that drive beaten out of us by negative attitudes or low expectations of well-meaning but uninformed professionals.”

Arielle’s extensive résumé illustrates her fierce commitment to empowering people with all kinds of disabilities and to eliminating the veiled attitudinal barriers that people with disabilities confront in their daily lives. When asked about disability sensitivity training, she offers a unique perspective on both the concept and the lexicon. “I think this type of education can be very good or very bad. A common stereotype about disabled people is that we are helpless or need to be treated delicately. The term ‘sensitivity,’ if misused, could reinforce that belief by implying that people need to take special care when interacting with a disabled person or need to hold us to lenient standards.”

Both Arielle and Sharona, however, believe that disability education is improving. But Arielle points out that markedly few educational programs on the subject are actually run by people with a disability. “After all, a program about racial equality or multiculturalism wouldn’t just include white American perspectives,” she says. “I hope that future disability education programs will involve people with disabilities as central contributors.”

Overall, Arielle does not find herself disabled by blindness because she has chosen environments in which she can use her intellectual skills and where she can surround herself with supportive people who consistently provide her with opportunities to succeed and thrive. That doesn’t mean that Arielle doesn’t struggle sometimes with blindness.

“While blindness usually doesn’t constitute disability for me, it can be very annoying at times,” she says. “For example, there is no great way for blind people to independently read maps, so I have to spend a lot more time gathering information to learn how to navigate from one place to another. I can still travel independently between two points; it just takes some persistence to gather the information I need.”

Arielle equates these small annoyances with other personal characteristics like not being tall enough to reach high shelves or dealing with reproductive issues as a woman.

Today, the only people who treat Arielle differently are people who don’t know her well. She classifies the undesirable interactions due to her blindness as often unintended but still insulting “micro-aggressions.” These include people grabbing or pulling her to “help” her get around, talking to her as if she cannot hear them or patronizingly praising her for mundane tasks like walking down the street without falling.

“I want people to treat me in exactly the same manner as they would treat a non-disabled stranger, which means you needn’t be either avoidant or overly friendly.” Furthermore, she advises, “If you are unsure if any disabled person is in need of assistance, it is best to directly ask them.”

Arielle grew up as part of Temple Chai’s Reform synagogue, and her family has always valued education, Jewish learning and ritual. She recounts being interested in Torah and prayer from a very young age and warmly remembers her father, Dr. Howard Silverman, reading her the entire Torah over the course of one year. While some aspects of Judaism seem to have lost their relevance for Arielle, she comments, “I still feel connected to what I believe are Jewish values such as loving kindness toward others, honesty, resilience and joy. I have always been driven to give tzedakah back to my community, and I believe that my professional choices are inspired by that goal.”

Sharona is proud of both Arielle’s and her older sister Rachel’s character and accomplishments. “We have worked hard to loosen expectations and to accept others for who they are,” Sharona says. “We have discovered that there are always ways to move toward wholeness and connectedness by being open to new possibilities.”